The following post are a paper that I wrote for my senior seminar class last year. It is a paper about a ship that sunk in the Chicago River. I am going to post the paper in parts just as I wrote it, this posting contains the introduction and Part I.

On July 24, 1915, The Western Electric Company charted

the Eastland, the Theodore Roosevelt, the Petoskey, the Maywood,

the Racine, and the Rochester to take 7,300 workers and their family

members from the Cicero, Illinois plant to a picnic in Michigan City, Indiana. The

passengers boarded the ship on the south bank of the Chicago River between

Clark and LaSalle Street, closer to LaSalle Street.[1] The excursion across Lake Michigan never took place due

to the tragedy that unfolded on the Eastland, when it capsized

trapping hundreds below deck and killing, according to George Hilton, 844

people. The Eastland disaster is the greatest loss of life in the city of

Chicago’s history. The Chicago River is

only twenty feet deep at the site of the disaster this helped minimize the loss

of life. To this day, it is uncertain to

whose shoulders the blame rests. Could

the lack of knowledge by the ship owner have caused the capsizing of the

ship? Was it due to being top-heavy, human error, a faulty

ballast system, or was it a combination of all three? In addition, Why is the Eastland all but

forgotten when it comes to disasters, in the City of Chicago? The following essay will examine these

questions and try to solve the mystery of why the Eastland capsized on that terrible day.

The

following is broken up into six sections; Background and Capsizing, Immediate

Aftermath, The Effects of the Disaster, History of the Eastland, Theories of Why it Capsized, and Why it is

Forgotten. This is because it will help

the reader have a better understanding of the material. By presenting the information in such an

organized manner, the reader is able to receive a more detailed and clearer

picture of the disaster. Finally, this

will facilitate one to make a more educated assessment of the disaster, the

cause, and the effects.

I.

Background

and Capsizing

The annual picnic was to be a

pleasurable trip for the workers of the Western Electric Company, as it was in

the past. The picnic began in 1881 as a

small, in-town occasion. However, this

changed in 1911 when workers founded the Hawthorne Club, with the goal of

“bringing the employees of various departments into closer association with

each other.” [2] Even though it

had no official affiliation to the company, the group had the support of many

of Western Electric’s senior management.

The Hawthorne Club organized different events from lectures to banquets,

and it was in charge of all social functions for the Western Electric Company

Hawthorne plant. The Hawthorne Club soon

turned its attention to the company picnic, which became the club’s main occasion

of the summer. The Hawthorne Club took

control of planning the 1912 picnic and for the first time in the history of

the picnic, they held the picnic out of town.

Three thousand five hundred workers attended the picnic held in Michigan

City, Indiana.[3] The picnic

continued to grow to include family and friends and just one year later the

number of people who attended the picnic practically doubled. In 1915, the picnic had reached a record

number of attendees. In addition, the

Hawthorne Club staged parades on company grounds in order to help promote the

picnic. The company had cut hours of

workers earlier in the year and there was a need for a morale boost, which the

parades provided. Some made claims that

when it came to buying tickets for the picnic, they had no choice. Additionally, some workers felt that they not

only have to attend the picnic but also had to buy multiple tickets in order to

keep their job at the plant. However,

this was not the case.[4] A few employees

believed that they had lost their jobs do to the fact that they had not

attended the picnic the previous year.

Superstitions such as these were quite common during this time.

Superstitions played a role in

everyday life in 1915; the immigrants who came to Chicago brought many of these

superstitions from the Old World.

Immigrants would cling to their old beliefs, as defense mechanisms in an

age of transition and change. A visitor

would notice the city streets as fortunetellers dotted the shops. There for it is not surprising that superstitions

played a role in the trip for the Eastland

as well.

The day before the excursion while

packing lunches for the picnic. Louise

Jahnke, the young bride of Paul Jahnke, had a horrible feeling that “something

would happen to the boat.”[5] After a night

filled with restlessness and weird dreams, the Jahnkes prepared for their trip,

but not before making a few arrangements.

The Jahnke’s approached their landlord and gave her their key and fifty

dollars, in case something were to happen to them. If something were to happen, Paul’s mother

would be able to stay in the apartment.

Louise also left a poignant letter attached to their will and stated

that she was leaving her bracelet and rings to her mother.[6]

Louise was not the only one to have

a premonition about the ill-fated trip that was before them. A visiting tourist, Mrs. J. B. Burroughs, woke

in the middle of the night from a dream, in which “a ship turned over on its

side, and hundreds of corpses lying in a row.”[7] Additionally,

there was an eighteen-year-old Western Electric employee, Josie Markowski, who moonlighted

as an amateur fortuneteller. The week

leading up to the excursion she was suffering from ‘flashes of dread’

throughout the week. The morning of the

trip she told a friend’s mother that something awful was going to happen on the

trip and that, she did not want to go to the picnic. Her friend’s mother laughed at her and told

her to go on the trip and to stop thinking about the disaster as she might bring

it on the boat with her.[8] These stories

leave an eerie feeling, as if a higher power was warning them not to make the

journey and to warn others of pending danger.

The excursion started at 5:30am when

Martin Flatow, port agent for the St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company, went

out to the river and discovered that it was 0.1 feet below its normal depth. Because the Eastland was a little heavier than it was in 1914 and sat a litter

lower in the water, Flatow decided to move the Eastland a little more eastward where the wharf was a little lower,

thus making the ship easier to load.[9] The bow of the

ship was sixty feet west of the Clark Street Bridge, and was unable to sail on

her own from the position from which she was setup to load. The Eastland

was moored with five lines that included three in the front and two in the

back. The only location passengers were

able to boarded the ship was at the stern of the ship, only one gangplank was

used. The ship began boarding at 6:40am.

It was estimated that there was already

five thousand people waiting to go on the excursion, double the number that the

Eastland could hold. The ship begin to list immediately to

starboard which is expected as this was the side of the ship that was being

boarded. The ship was boarded at a rate

of 50 passengers per minute, which is a very fast pace with only one gangplank.[10]

Immediately below and as labeled

Figure 1 is a picture of eager passengers waiting to board one of the many

ships for the excursion on July 24. It

was taken early in the morning, around 6:30 a.m. Many of these individuals were aboard the Eastland when it sank. As the picture shows there is a large group

of people waiting to get down to the riverfront. In addition, there is a police presence, to

help control and direct the crowd of people.

This picture does not show all the people that were going to attend the

picnic, as the last ship was to leave around 2:30 p.m. There are also many people down on the dock

boarding the ship at this time. In addition, in the background one is able

to see that there are still many people coming to the dock. Therefore, this picture is not an accurate

representation of the quantity of passengers waiting to embark on the excursion.

Figure 1 People gathering to board the ships

at 6:30 a.m.

Immediately

below and labeled Figure 2 is an artist painting of the view from the Wells

Street bridge, which is just one block west of where the Eastland capsized. Even

thought the painting is eleven years before the disaster it helps one to visualize

what the area looked like around the time of the disaster.

Figure 2 Artist painting of the Eastland

docked just south of the Wells Street Bridge.

On the deck of the Eastland, no one seemed very concerned

about the ship listing back and forth, as this was nothing out of the ordinary.

Captain Harry Pedersen had no fears that there was something wrong so

why would the passengers worry? Nevertheless,

at 7:19am the engine room was a buzz because Joe Erickson, the Chief engine

room officer, and the engine room crew thought that they had they begun to gain

control of the listing Eastland. As water continues to rush into the starboard

ballast tanks, the ship began to right herself.

Erickson was correct, the ship was returning to zero degrees, or even

keel. When a ship is parallel with the

water it is considered to have a zero degree list. A ship must lean port or starboard to have a

list other than zero, when this happens a ship has a list of said degrees port

or starboard. The Captain of a ship

wants the ship to have a zero degree list.

At this time, Harbormaster Adam Weckler told Captain Pedersen that he ‘could

have’ the bridge whenever he wanted. Weckler would open the bridge when Captain

Pedersen was ready to leave. At once, Captain

Pedersen gave his First Mate the order to ‘stand-by’, which meant they were

ready to cast-off.[13] At 7:20 a.m. the

ship had reached its passenger capacity of two thousand five hundred people, only

forty minutes after it begin loading. With

crewmembers of the Eastland drawing in the gangplanks, E.W. Sladkey came upon

the ship and was encouraged to jump on the ship by some of his fellow workers. Sladkey was happy to oblige his coworkers and

as if on cue the boat begin to list. It

was as if the last passenger had made a big difference in the boat’s stability.[14]

Harbormaster Weckler was walking

away towards Clark Street, but he stopped once he saw the ship list again. Weckler stared at the ship for a few minutes when

he noticed, Charles Lasser casting off the mooring lines. Weckler forced his way through the crowd to

get to Lasser, Weckler told him to stop casting off the lines.[15] Weckler understood

that the boat was probably overloaded, and seemed to be having some trouble

with the ballast. Weckler then stormed

back toward the wheelhouse, and once he got within earshot of Pedersen, Weckler

began yelling to “trim her up,” as the ship was now listing 10 degrees port. Weckler informed Pedersen that the ship would

not leave until she was trim.

The ship began to take on water

through the scupper; Erickson ordered to his men to “Stop the engines! ALL STOP NOW!”[16] Still passengers

took little notice of the ship as they were enjoying themselves. At a list of 20 degrees portside, the ships

refrigerator tipped over along with glass bottles from the bar, this still did

not create a panic on the ship.[17] Crewmembers

began asking the passengers to move to the starboard side of the ship and they

began doing so without any complaints or panic.

At 7:25, the ship temporarily returns to even keel. However, the panic that had just set in as

water come aboard was now subsided. The

band picked back up their instruments and began playing again as if nothing

happened.[18] The ship began a

port list again 20 degrees then 25 degrees then 30 degrees, while crewmembers continued

to escort people to the starboard side of the ship. An onlooker, Mike Javanco, anticipated what

was about to happen to the ship and called out “Get off! Da Boat’s turin’ over!” One of the passenger on the ship yelled back

“Go on, Dago! You’re crazy.”[19] The ship was now

listing 35 degrees to port, and then suddenly righted herself as if it changed

her mind about tipping over. However, at

7:30, the boat began to list again this time to 45 degrees to port, and the

band stopped playing in the middle of a note. As chairs and other non-stationary objects

began to move, passengers starting grabbing for the nearest stationary object

and were holding on for dear life.

Others who had nothing to grab on to went sliding toward the water. Members of the crew went running to

companionways, and began exiting the doomed ship. They left the helpless passengers to fend for

themselves.[20]

Both on the ship and on the docks a

sudden panic came over the passengers and the on-lookers. Captain Pedersen, finally coming to the

realization that the situation was utterly unpromising, yelled down to have a

crewmember open his gangway. Passengers

begin jumping out the half open door, and panic spread like a wild fire among

the passengers and crew. The crew and

passengers were jumping off the starboard side on to the wharf or into the river. Nevertheless, it was too late. All of the jumping simply just made matters

worse, as the already lighter starboard side was getting lighter as people

jumped. On the dock, an eerie feeling came

over the crowd as they watched the Eastland

list back and forth. Traffic stopped and

the passengers on other ships looked on in horror. The band on the Roosevelt stopped in the middle of a song as people froze aboard

the ship.

The ship continued a port list

reaching fifty degrees. At this time on

the ship, the only crewmember met his death.

The piano slid off the stage and killed Willie Guenther, a member of the

band, instantly as it crushed him against the wall. Water came pouring into the ship, making the

weight of the ship even more unbalanced then it already was, this only sped up

time until the ship made its deadly fate.

It was everyone for themselves at this point; the strong were overtaking

the weak as they tried to get off the ship through any opening they could find. This ship had reached a point of utter and

complete chaos.

From this point, there was no chance

for the ship to right herself. One of

the first people to come to this conclusion was Joseph R. Lynn, the assistant

harbormaster. At 7:24, Lynn went down to

the wharf to test the three moored lines on the front of the Eastland. He then used the building around the ship to estimate

the port list and concluded that the ship was doomed. He then proceeded up the Clark Street Bridge

stairs to Weckler and explained that the fate of the ship was hopeless. Lynn then proceeded to call the Chicago Fire

Department. John Lescher, a Chicago

Policeman overlooking the boarding of the ships, came to the same conclusion as

Lynn. Lescher ran to the Clark Street

Bridge and up the stairs, and turned in an alarm to the police department.[21] Before the ship was

even in the water help was on the way.

In less than one minute, the Chicago

River became polluted with bodies of those whom jumped or were thrown from the

ship. Harry Miller, a crewmember,

watched a woman with a baby in her arms go overboard and he decided to go after

her. He would later state to the New York Times,

I jumped in

after her to get her. In less than a

second, [passengers] began dropping in all around me. There must have been hundreds of them that

jumped in. The water was thick with

them. One hit me on the shoulders and

drove me under.[22]

The

ship took less than two minutes to capsize into the Chicago River. Fred G. Fischer, who was a traffic police

officer assigned to watch over the loading process, stated “[the Eastland] just turned over like an egg

in the water” the ship made little to no splash in the water.[23] The time was

7:30 a.m. nearly, an hour after the ship began boarding. The day for everyone involved went from

pleasure to a day of remorse. George

Dubeau, a passenger on the S.S. Theodore

recalled:

It was a

terrible sight—men and women and children being plunged into the water and all

screaming. In one minute, the water was

full of people with only their heads above water and calling to be saved—that

is, those who did not sink at once. [24]

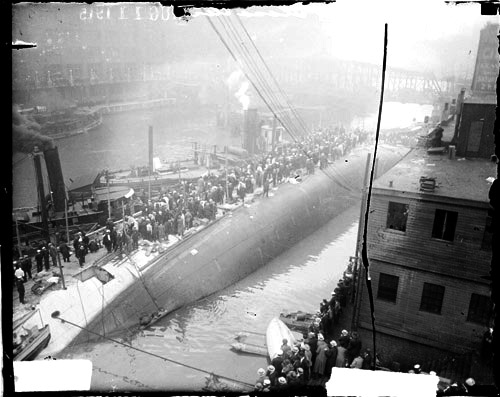

Immediately below and as labeled

Figure 3 is a picture of both survivors and rescuers standing on the

hull of the Eastland after the ship

capsized in the Chicago River, and as rescue attempts continue.

Figure 3 View of both survivors and rescuers on the hull of

the Eastland

[1] George W Hilton, Eastland:

Legacy of the Titanic. (Stanford: Stanford University

Press, 1995), pg vii.

[2] Jay Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland: America’s Forgotten Tragedy. (New York: Citadel Press, 2004), pg 29.

[3] Bonansinga, The Sinking of

the Eastland, pg 29.

[5] Chicago Tribune 7/27/15, cited in

Bonansinga,

The Sinking of the Eastland, pg 21.

[6] Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland, pg 20-22.

[7] Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland, pg 22.

[8] Chicago Tribune July 27, 1915, pg 7

cited in Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland,

pg 22.

[10] Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, pg 95.

[11] Chicago

Daily News, published in the newspaper between July 24-August 13, 1915. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News negatives

collection, DN-0064970.

[12] John Chuckman, “Steamer Eastland– Wells Street Dock – Later Sunk– 1908,” http://chuckmanchicagonostalgia.wordpress.com/2009/10/15/steamer-eastland-wells-street-dock-later-sunk-1908/, October 15, 2009 (accessed November 1, 2010).

[13] Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, pg 102.

[14] Hilton, Eastland:

Legacy of the Titanic, pg 103, also cited in Bonansinga, The Sinking of

the Eastland, pg 54-6.

[15] Bonansinga, The Sinking of the

Eastland, pg 56.

[16] Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, pg 104, also cited in Bonansinga,

pg 58.

[17] Transcript of

testimony, Coroner's inquest, pg 3. Cited in Bonansinga, pg 59.

[18] Bonansinga, The Sinking of the

Eastland, pg 62.

[19] Chicago Tribune, 7/25/15, pg 12

cited in Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland, pg 66.

[20] Bonansinga, The Sinking of the

Eastland, pg 66-69.

[21] Chicago

Evening Post, July 27, 1915, pg 4. Cited in Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, pg 113.

[22] New York Times, “Saw Hundreds Fall to Death in River; Deck Hand Tells of the Panic --

Stairways Jammed -- Swimmers Dragged Under.” July 25, 1915, pg 1

[23] Chicago

Evening Post, July 27, 1915, p 4. Cited

in Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the

Titanic, pg 109.

[24] Ted

Wachholz, Images of America; The Eastland Disaster. (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), pg 45.

[25] Chicago Daily News, July 26, 1915. Courtesy of The Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News negatives

collection, DN-0064944.

Gotta love good old chicago history! They used the excaleber night club building as a mortuary among other place for the masses of victims.

ReplyDelete